Raising Your Own Queens – Sustainably, Locally, and Without Imports.

To empower British beekeepers to rear locally adapted queens through On-The-Spot methods, strengthen Apis mellifera mellifera populations, and end reliance on imported bees.

ABOUT OTS

About the OTS Method

On-The-Spot Queen Rearing for Sustainable, Locally Adapted Beekeeping

Origins of the OTS Method

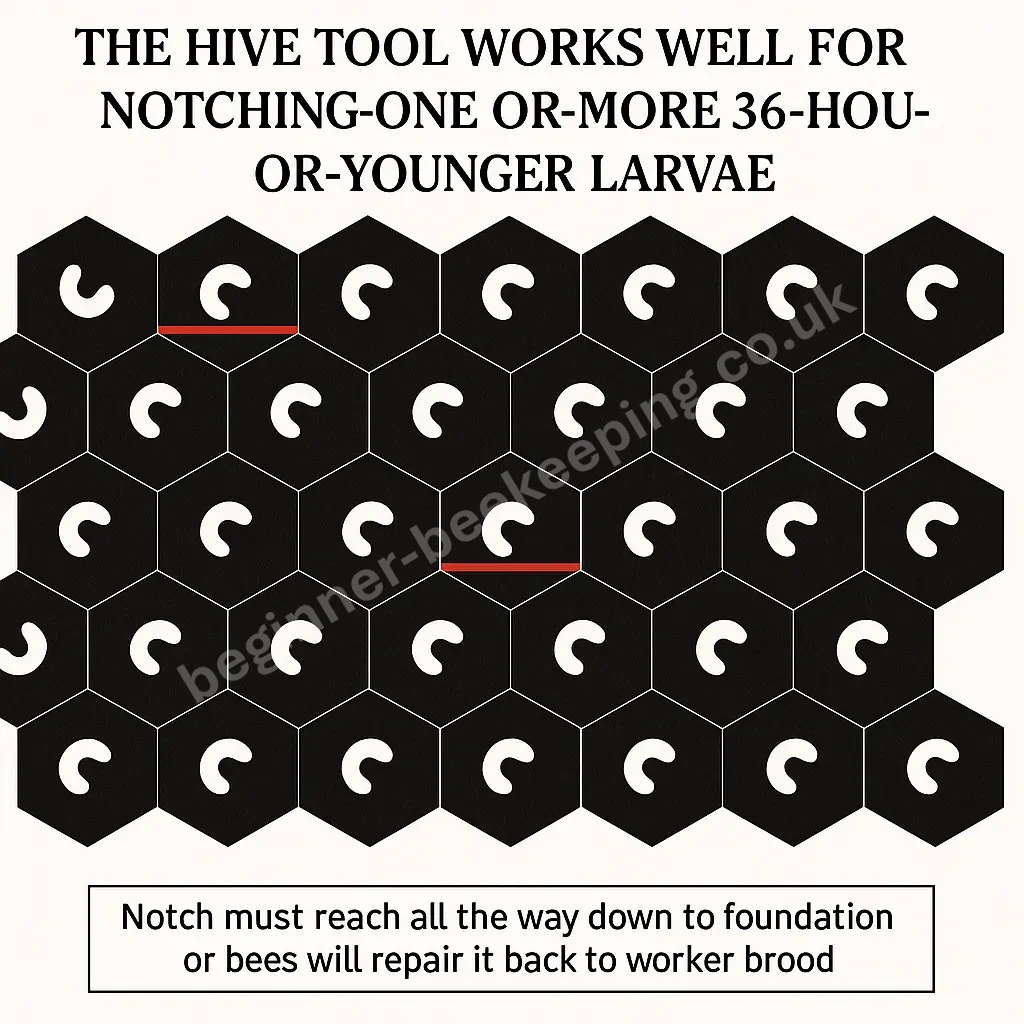

The On-The-Spot (OTS) queen-rearing method was developed by Mel Disselkoen in Michigan, USA. It provides a simple way for beekeepers to raise quality queens without grafting or special equipment. The technique relies on “notching” the cell wall below very young larvae (under 36 hours old) so that bees respond by building emergency queen cells. These cells produce well-fed, naturally selected queens that can replace failing queens or expand the apiary.

The OTS Principle

Disselkoen’s insight was that by mimicking a colony’s natural response to queen loss, a beekeeper can guide bee behaviour without artificial grafting. A strong, queenless colony will rear new queens quickly, ensuring a steady supply of locally adapted queens and interrupting the brood cycle – a key benefit for Varroa management.

OTS in the UK Context

While OTS was designed for North American climates, its principles adapt beautifully to British conditions. In Yorkshire and across the UK, OTS fits within the natural spring swarming season (May–June), when colonies are at peak strength and drones are abundant for mating.

However, for a sustainable British approach, the goal is not rapid multiplication for sale or large-scale splits. Instead, OTS should be used to maintain healthy, self-replacing colonies of locally adapted bees, reducing dependency on imports and conserving the genetics of our native Apis mellifera mellifera.

OTS and Sustainability

The original OTS system encourages frequent increases and splits, which can sometimes weaken local populations if overused. In the UK, a balanced method – blending OTS with selective breeding and Darwinian beekeeping principles – ensures that bee populations grow naturally and sustainably.

Our Philosophy

WHY LOCAL QUEENS MATTER

Why Local Queens Matter

Strengthening Britain’s Bees through Local Adaptation and Sustainable Breeding

The Importance of Local Genetics

Locally bred queens are the cornerstone of sustainable beekeeping. They are adapted to the specific weather patterns, flora, and diseases of their environment. Research across Europe has shown that colonies with local-origin queens live longer and overwinter more successfully than imported stock.

In a landmark European study on colony survival, locally adapted colonies survived on average 83 days longer than imported equivalents, highlighting how genetic-environment compatibility directly affects bee health. By rearing queens within your own apiary using OTS, you harness the principle of natural selection – ensuring only the fittest lines continue.

Native Bees of the British Isles

The native European Dark Honey Bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) evolved over millennia to thrive in the cool, damp climates of the British Isles. Darker, hardier, and frugal with winter stores, these bees have a unique resilience unmatched by southern or Mediterranean imports.

Unfortunately, the genetic integrity of AMM has been diluted by decades of queen importation – a practice that introduces foreign lineages less suited to UK conditions. Every locally reared queen helps restore that balance and strengthens our national bee heritage.

The Risk of Imports

Imported queens are often marketed as “gentle” or “productive,” but they bring hidden risks. They may carry new diseases or mites, and their offspring often struggle to survive UK winters or forage effectively in northern climates. Over-reliance on imported stock also weakens local resilience and contributes to genetic homogenisation.

- Disease risk: Imported bees can introduce pathogens and parasites (as highlighted by UK biosecurity experts and the National Bee Unit).

- Loss of adaptation: Crossbreeding can erase hard-won local traits like thriftiness and weather tolerance.

- Dependency: Reliance on imported queens undermines beekeeper independence and biosecurity.

OTS and Local Breeding

The On-The-Spot (OTS) method enables any beekeeper to raise replacement queens from their own strongest colonies – those that have survived local winters, resisted Varroa, and thrived in nearby forage conditions. Instead of buying in new genetics, the OTS system lets your bees teach you what works best in your environment.

For a sustainable approach to OTS, limit queen production to what your local forage can support. Prioritise quality and survival over numbers. By raising queens from proven local stock, you become part of the solution – reducing imports, supporting biodiversity, and strengthening the genetic continuity of Britain’s bees.

Our Vision

THE UK OTS METHOD

The UK OTS Method

Adapting On-The-Spot Queen Rearing for Sustainable Beekeeping in the British Climate

Adapting OTS to the British Climate

The On-The-Spot (OTS) queen-rearing method provides a simple, equipment-free way to rear queens. In the UK, our cooler, variable climate means timing and stock selection are crucial. Colonies should be managed to follow natural seasonal rhythms – using the OTS method to encourage resilience rather than industrial-scale increase.

The Yorkshire climate, with its late springs and unpredictable summers, requires close observation of colony buildup. OTS should begin only once colonies are brimming with bees and drones are flying freely. Typically, this falls between late May and early July, depending on regional variation.

Step-by-Step: The UK OTS Calendar

This table outlines how to apply OTS safely and effectively through the beekeeping year in British conditions.

| Month | Action | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| April | Inspect overwintered colonies; mark strong survivor colonies for potential queen mothers. | Select from locally adapted, disease-resistant stock (following Pritchard’s principle of “breed from the best, eat the rest”). |

| May | Prepare colonies with good brood and stores. Choose one strong colony to notch. | Ensure colonies are populous enough to respond vigorously to queen loss. |

| June | Perform OTS notching under larvae < 36 hours old. Remove queen from cell-builder colony. | Trigger emergency queen cell production without grafting. |

| Late June | Transfer queen cells into nucs or smaller colonies after 8–9 days. | Allow new queens to emerge and mate during peak drone availability. |

| July–August | Introduce mated queens to requeen weaker colonies or create nucleus colonies. | Requeen after main nectar flow to ensure stable winter colonies. |

| September | Assess new queens’ brood patterns; unite weak colonies or overwinter strong nucs. | Prepare colonies for winter with healthy, locally bred queens. |

For a Sustainable Approach to This…

Over-expansion weakens local drone pools and risks overstocking forage. Instead of aiming for quantity, raise fewer, higher-quality queens selected for overwintering ability, frugality, and gentle temperament – traits that define the native Apis mellifera mellifera bee.

Biological Rationale and Varroa Management

When used carefully, OTS creates a brood break during the colony’s queenless period. This interrupts the Varroa reproductive cycle, echoing what Dr. Ingemar Fries described as a key factor in host-parasite co-adaptation in untreated populations.

The aim is not to “control” Varroa through chemicals but to select for bees that cope with it naturally, as advocated by Tom Seeley’s concept of Darwinian beekeeping – allowing natural selection to restore balance between bee and mite populations.

Environmental Factors in the UK

Willie Robson’s long experience in Northumberland reminds us that bees must be sheltered, well-fed, and never over-stressed. Choose sunny, wind-protected apiary sites with nearby forage throughout the year. Pollen availability is crucial – insufficient protein in early spring will undermine the success of any queen-rearing program.

Encourage floral diversity: early pollen sources (willow, crocus, dandelion), summer nectar (clover, lime, bramble), and late forage (ivy, heather) to sustain your colonies through all stages of the OTS cycle.

Line Breeding and Local Selection

Dr. Dorian Pritchard advises that successful bee improvement depends not on importing new blood, but on refining what already thrives locally. By rearing queens from survivor stock and mating them locally, you confine breeding to a consistent, well-adapted gene pool – improving it generation by generation.

Final Thought

SUSTAINABLE BEE BREEDING

Sustainable Bee Breeding

Building Resilient, Locally Adapted Bee Populations for the Future

The Purpose of Sustainable Bee Breeding

Sustainable bee breeding is about working with nature, not against it. It draws from the principles of local adaptation, genetic integrity, and ecological balance. The aim is to build colonies that can survive and thrive in your environment without reliance on chemical treatments, imported queens, or artificial feeding regimes.

In the UK, this means prioritising our native and near-native Apis mellifera mellifera – the European dark bee – whose genetics are already finely tuned to Britain’s climate and forage cycles.

Principles of Sustainable Bee Breeding

- Local Adaptation: Breed from colonies that overwinter successfully and thrive without treatments.

- Minimal Intervention: Allow natural selection to shape colony resilience.

- Genetic Integrity: Avoid hybridisation with imported stock; maintain a pure or near-pure native line.

- Nutrition and Ecology: Support colonies through diverse forage and soil health – not sugar syrup.

- Community Cooperation: Share genetics and data within your local area to stabilise bee populations regionally.

Line Breeding: Refining the Local Strain

Following Dr. Dorian Pritchard’s approach, sustainable breeding focuses on careful line breeding within a defined population rather than outcrossing with unrelated or imported stock. This maintains local adaptation while allowing gradual improvement in key traits:

- Temperament – gentle, steady, and workable.

- Frugality – minimal winter stores consumption.

- Disease resistance – natural Varroa tolerance through selection and brood breaks.

- Colony cohesion – strong queen pheromone and low swarming impulse.

– Dorian Pritchard, Breeding Honeybees on a Small Scale

Nutrition: The Foundation of Bee Health

As Professor Robert Pickard reminds us, nutrition is an atomic and ecological process: all life depends on the circulation of elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon through ecosystems. In beekeeping, this translates to maintaining diverse forage and soil biology so bees have access to balanced pollen and nectar sources throughout the year.

A sustainable breeder ensures bees feed from varied native plants – willow, dandelion, clover, bramble, heather, ivy – not just monocultures. Such diversity strengthens immunity and encourages symbiosis with beneficial microbes, echoing Pickard’s view that “nothing survives without the microorganisms.”

Natural Selection in Practice

Sustainable bee breeding embraces Darwinian Beekeeping – Tom Seeley’s vision of allowing natural selection to do the work of resilience. Colonies that survive without treatments or imports are the foundation of a self-sustaining beekeeping future.

Research by Ingemar Fries and others confirms that, given isolation and time, bee populations develop host-parasite balance with Varroa. Survival in untreated colonies is evidence that adaptation is possible if we stop interfering.

– Tom Seeley, Darwinian Beekeeping

Biosecurity and the Threat of Imports

Importing queens undermines local adaptation and invites new pathogens. As Professor Mairi Knight showed at the B4 Symposium, over 30,000 imported queens enter the UK each year – mostly from Mediterranean C-lineage stock. These bees are poorly suited to our cool climate and risk introducing new parasites like Tropilaelaps mites:contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}.

By breeding locally and sharing stock within your region, you help close the genetic and epidemiological borders, building what Knight calls a “biosecure, self-renewing beekeeping culture.”

– B4 Symposium, 2025

Working Together for a Local Future

Sustainable bee breeding succeeds when beekeepers cooperate rather than compete. Create small, regionally connected networks where drones and queens share a genetic landscape. Each local group can become a breeding island – an informal conservation area for the native bee.

- Exchange data on queen survival and temperament.

- Form drone-saturated mating zones using local colonies.

- Host OTS workshops to encourage local requeening over imports.

Final Thought

CONSERVATION AND BIOSECURITY

Conservation and Biosecurity

Protecting Britain’s Bees from Imports, Disease, and Genetic Erosion

Why Conservation Matters

Every bee colony in Britain is part of a fragile ecological network. Our honeybees, wild pollinators, and native plants evolved together over millennia – forming a balanced, interdependent system. Protecting that balance is at the heart of sustainable beekeeping.

The goal of conservation beekeeping is not simply to keep colonies alive, but to preserve the genetic integrity and ecological role of the European dark honey bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) – Britain’s native honey bee and the most climate-fit subspecies for the Isles.

The Threat of Imports

Over 30,000 queens are imported into the UK annually, mainly from Italy, Malta, and Slovenia. These imports belong to the C-lineage of European honeybees – genetically distinct from the northern M-lineage that includes our native AMM. Each imported queen weakens local adaptation and increases disease risk.

Despite post-Brexit regulations banning imports of packages and nuclei, the “Northern Ireland loophole” continues to allow entry of thousands of queens unmonitored by mainland inspection. Diseases like Varroa destructor, Small Hive Beetle, and new viruses all entered Europe through trade.

Emerging Threat: Tropilaelaps

In 2024, Tropilaelaps mites were confirmed in southern Europe for the first time. These mites reproduce faster than Varroa and cause greater damage to brood. Originally confined to Asia, they have adapted to Apis mellifera and are spreading rapidly through trade and climate expansion.

Unlike Varroa, Tropilaelaps cannot survive without brood for long – meaning the UK’s cooler winters may slow their spread, but only temporarily. The simplest defence is biosecurity through isolation: reducing imports, maintaining clean apiaries, and supporting local breeding.

Wild Colonies: Nature’s Breeding Reservoir

Studies show that wild honeybee colonies act as vital reservoirs of genetic diversity and natural disease resistance. In unmanaged settings, natural selection favours bees with innate defences against mites, viruses, and climatic stress – the traits that imported commercial lines often lose.

Conservation-minded beekeepers can protect these wild genes by:

- Leaving feral colonies undisturbed.

- Breeding queens from colonies that survive unaided for multiple seasons.

- Reporting and monitoring wild nests for research.

Practical Biosecurity in the Apiary

- Do not import bees or queens – source locally bred stock only.

- Maintain clean equipment: disinfect hive tools and gloves between colonies.

- Quarantine new colonies for at least six weeks before integration.

- Practice closed breeding: keep drones and queens within a defined local population.

- Monitor regularly: perform sugar rolls, drone brood checks, and visual inspections.

- Share data: collaborate with local groups (BIBBA, B4, or regional AMM networks).

Ecological Conservation and Forage

Conservation extends beyond genetics and pests. Bee survival depends on habitat: continuous nectar, clean water, and diverse pollen. Sustainable apiaries promote forage corridors through wildflower sowing, hedge restoration, and avoidance of chemical pesticides.

Protecting wild forage protects all pollinators – honeybees, bumblebees, and solitary species alike. In return, bees maintain the biodiversity that underpins our agriculture and wild flora.

For a Sustainable Approach to OTS

Each queen raised locally contributes to a self-sustaining bee population, reducing the demand for imports and reinforcing regional adaptation.

Final Thought

RESOURCES

OTS was designed to make beekeepers independent of commercial queen suppliers. In the UK, we take it a step further – using OTS not for industrial-scale production, but for ecological self-sufficiency. Each queen raised locally strengthens our bees’ genetic link to their environment, securing the future of British beekeeping.