Setting the Scene: Why Imports Matter

For over 20 years, Professor Mairi Knight has worked with bees – first with bumblebees, and more recently with honey bees through long-term collaborations with B4 (Bees for Development). In her opening talk at the recent B4 Conference, she outlined the scale and implications of honey bee imports into the UK.

Her presentation provided crucial context for later talks exploring disease transmission, genetics, and sustainable solutions for British beekeeping.

Why Are Honey Bees Imported?

Beekeepers across the UK import tens of thousands of honey bee queens every year – and this number has been rising dramatically since 2007. But why? Professor Knight identified several overlapping reasons:

- Shortage of locally reared queens – Many regions lack sufficient supplies to meet demand.

- Increased interest in beekeeping – A surge in new beekeepers has created pressure on domestic breeding.

- High overwintering losses – Cold weather, varroa infestations, and disease outbreaks lead to queen losses that must be replaced each spring.

- Early-season supply – Mediterranean countries can rear queens earlier in the year, allowing UK beekeepers to restock quickly.

- Low cost and online convenience – Ordering a queen bee online for £30 – £50 is quick, easy, and appealing to hobbyists.

- Perception of “better bees” – Imported bees are sometimes believed to be more productive or docile – though this belief is increasingly being challenged.

“It’s cheap, it’s convenient, and it’s easy to do – but people don’t always realise the potential problems associated with it,” Professor Knight warned.

What Are the Current Import Controls?

Since Brexit (2021), new regulations have restricted the import of honey bee nuclei and packages into Great Britain. However, importing queen bees – each accompanied by a few attendant workers – is still permitted under strict conditions.

- Queens must be registered and tested by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) or SASA in Scotland.

- However, testing resources are limited, meaning that only a small proportion of imported bees are screened for disease – a growing cause for concern.

- A Northern Ireland loophole also allows bees to enter Great Britain indirectly via the EU single market, further complicating disease tracking and control.

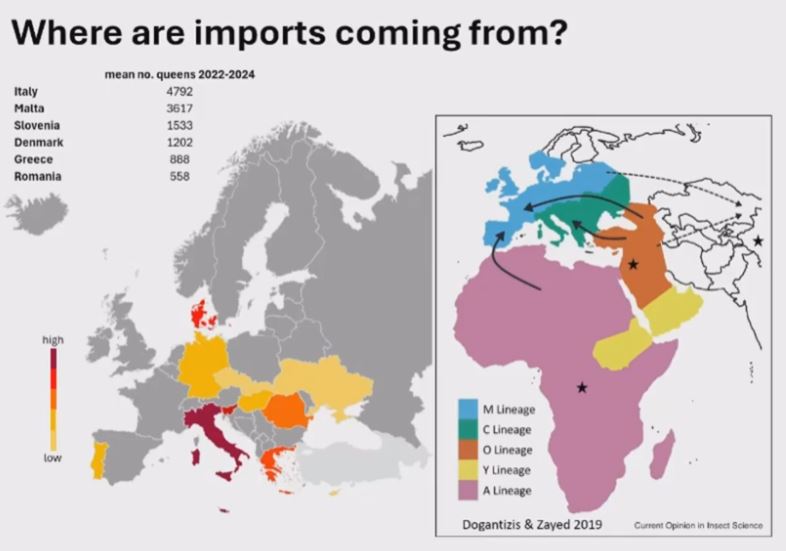

How Big Is the Import Market?

Official figures show a fourfold increase in honey bee imports since 2007 – from around 7,000 queens to over 30,000 by 2024.

While official UK imports appear to have plateaued, many bees now enter through Northern Ireland, masking the true scale of movement.

Where Do Imported Bees Come From?

According to 2024 National Bee Unit (NBU) data, most imported queens come from southern Europe, particularly:

- 🇮🇹 Italy

- 🇸🇮 Slovenia

- 🇲🇹 Malta (many via Northern Ireland)

- 🇬🇷 Greece

- 🇩🇰 Denmark

These regions share one key feature: they belong to the C-lineage of honey bees (Apis mellifera ligustica and carnica) – non-native to Northern Europe. The UK’s native honey bee, Apis mellifera mellifera (the dark European honey bee), belongs to the M-lineage.

This genetic mismatch poses long-term risks to native bee conservation, local adaptation, and colony resilience.

Why the Rise in Imports?

Several converging factors explain the rapid increase:

- Growing demand from expanding beekeeper numbers.

- Commercial opportunity – individuals importing large batches to resell within the UK.

- Convenience culture – online purchasing makes it effortless to source foreign queens.

- Climate and breeding cycles – southern European climates allow earlier queen production and export.

However, as Professor Knight noted, the very factors that make imported bees attractive – cost and accessibility – may also make them a hidden risk to UK biosecurity.

The Risks of Honey Bee Imports

Professor Knight highlighted three main threats:

- Introduction of new pests and pathogens – Including exotic diseases and varroa-resistant strains.

- Genetic homogenisation – Loss of locally adapted traits and dilution of native Apis mellifera mellifera genetics.

- Increased winter mortality – Imported queens and colonies often struggle in the UK’s cooler, wetter climate.

She stressed that while imports may meet short-term demand, they could undermine the long-term health and resilience of British bees.

Moving Forward: A Balanced Approach

Professor Knight concluded with a pragmatic message: any solution must balance bee health, beekeeper needs, and practical realities. Overly rigid bans or restrictions risk driving imports underground.

Instead, she called for:

- Support for local queen rearing programmes

- Greater transparency and traceability

- Improved disease testing capacity

- Education and awareness around the hidden costs of convenience

“We need solutions that work for beekeepers – otherwise people will simply find loopholes. A positive, practical approach is essential,” she said.

Key Takeaway

Honey bee imports to the UK continue to rise – driven by demand, convenience, and cost – but they come with real ecological and biosecurity risks.

Building capacity for locally bred, resilient, and well-adapted bees is the sustainable way forward. As the B4 Conference made clear, protecting our pollinators means thinking beyond short-term supply and safeguarding the future of British beekeeping.